|

|

| 03-05 |

| -個から総体へ- |

| 浪合フォーラム |

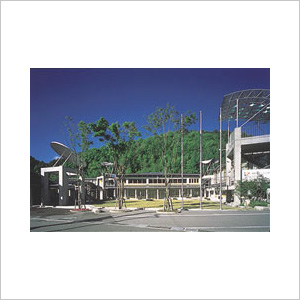

| Namiai Forum Village Center |

|

|

| 外山義福祉計画監修 |

| 長野県阿智村 |

| 公民館、役場庁舎、健康福祉施設の複合施設 |

| 1997年3月竣工 |

| 4000m2 |

| 木造RC混構造2階建て |

|

| 2000年 日本建築家協会環境建築賞 |

| 1999年 日本建築学会作品選奨 |

| 1996年 東京建築賞最優秀賞 |

| 1996年 日本建築士会連合会賞優秀賞 |

| 1993年 SDレビュー入選 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 写真:堀内広治 |

■浪合村は「村全体が村民すべての浪合学校」のコンセプトであたらしい村づくりを行った。

この建築ではソフトなサスティナビリティとして村づくりから続けたアクティビティニーズから建築プログラムへの検討、村の中心のありかた、

変更しながらつくるプロセスに対応する短冊型システムの提案、周辺の集落と調和した小さな単位の集合、木造建築の公共施設への提案、

零下15度の厳寒の風土に省エネ型建築の提案などを行い、建築、自治体関係者からの高い評価を頂いている。

■この村づくりの考えの元に、浪合学校と連携して村の中心をつくる複合施設をつくった。

■村の家並みと調和し、計画のフレキシビリティをもった6mスパンの平行ハーフボールトと中庭の空間構造を持つ。

■断熱気密性能を高め、零下15℃の厳寒の風土に対応し、木造の環境建築を創った。

■日本の伝統的都市空間の奥の思想にならい、奥に高く、大きな、人々をひきつける空間を配し、木造の100人ホールをつくった。

■永田穂氏の監修を得て、高い天井、平行壁のない、音響の良い空間を設計した。年間120回も利用されている。

|

| ▽次の文章はASIA WEEKに掲載のための島塚容子氏の原稿である。 |

| ■ ASIA WEEK(May 11,2001) Article written by Ms.Yoko Shimatuka, prepared

for ASIA WEEK |

IIt was a turning point for architect Ben Nakamura (54) when he got involved

in a public facility project in Namiai village in Nagano in the late 80s.

Nakamura, who was trained in modern architecture, felt uncomfortable designing

state of the art architecture in the countryside. He had seen many cases

where buildings were left unused after the local government spent millions

of yen on projects because it didn’t fit the climate or people’s lifestyle. IIt was a turning point for architect Ben Nakamura (54) when he got involved

in a public facility project in Namiai village in Nagano in the late 80s.

Nakamura, who was trained in modern architecture, felt uncomfortable designing

state of the art architecture in the countryside. He had seen many cases

where buildings were left unused after the local government spent millions

of yen on projects because it didn’t fit the climate or people’s lifestyle.

In snow country like Nagano, people used to gather around kerosene stoves in small rooms with low ceilings. Nakamura wanted to create openness using high beams for health reasons. For one, burning kerosene in a closed room can cause carbon monoxide poisoning. He spent two years talking to Namiai villagers and sketched out a model that would coexist with the environment and the people. He used plenty of natural resources in the building to express that image, at the same time focusing on energy conservation.

But when it came time to procure the material he needed, he ran into a problem of cost. Ecologically friendly buildings usually cost 1.5 times more than regular buildings because such materials aren’t mass-produced. Nakamura decided to be creative in overcoming that problem. He used glass from Thailand instead of using glass made in Japan. He found a mid-sized supplier who produced double pane windows for the price of the single pane window that big suppliers made. He used wood instead of aluminum window frames to keep the house warmer and also to cut down on the carbon dioxide output. Aluminum frames produce 340 times more carbon dioxide than wood frames during the manufacturing process. “I wanted the building to be energy efficient. I wasn’t thinking ecology entirely then, but I was actually doing it,” reflects Nakamura.

Since then, Nakamura became more aggressive about designing ecological friendly buildings. He uses more insulation and natural materials. And he re-uses rain and well water in some of his projects. Now, he’s even developing his own parts such as a joint to connect post and beam structure to hold three storage homes and pillars that are based on wood. Throughout his experience, Nakamura managed to design green buildings at the same cost of regular buildings. “If taking normal steps, it cost more for green buildings so you just have to be more creative,” smiles Nakamura.

Over the past few years, Nakamura gained recognition in the construction industry for his work as the industry became more interested in green buildings. Last year, he received an environmental building award sponsored by Japan Institute of Architects for his Namiai Village project.

Although many architects are interested in designing greener buildings, not all architects can do what Nakamura did. The general feeling among architects is that green building cost more and is time consuming. “I am interested in ecology buildings and am trying to use natural material instead of non-recyclable material for insulation, using coal under the floor to take out moisture, but in general, it’s difficult to find craftsmen who know the techniques and to find affordable materials,” says an architect Masayuki Asabuki.

Some younger architects think going green may limit their creativity because green building is considered un-sexy. Nakamura is trying to change that sentiment by educating his fellow architects through the Environmental Architecture Action Committee where he sits as the chair.

While the problem of cost and time remain a concern, Japanese are slowly turning green. One major reason behind the move, the government is pushing for regulations to protect the environment, use less energy and recycle more waste. A global trend to move toward ecology friendly societies is changing sentiment among people too.

Japan’s Agency of Natural Resources & Energy has been trying to promote

the use solar energy by giving subsides since fiscal 1994, amounting to

65.8 billion yen doled out to about 60,000 households by fiscal 2000. It's

a small number considering that there are about 45 million households in

Japan, but demand for solar-cell generator is on the raise. About 50,000

households are expected to receive aid for the system in the fiscal year

starting in April. That’s double the number who received aid last year.

“If we get 100,000 homes to use photovoltaic generators annually, we’ll

reach our goal of 420 mega watt in 10 years,” says Hiroto Arai, Deputy

Director of the agency’s New and Renewable Energy Division. The plan was

expected to end after fiscal 2002, but the agency is considering measures

to extend the program to boost users.

|

| 文: 島塚 容子 |

| ASIA WEEK |

|

ASIA WEEKの記事Home Pageは下記following adress を参照してください。

http://www.asiaweek.com/asiaweek/magazine/artsciences/0,8782,108626,00.html |

|